Big Men And Little Wars: The 200-Year-Old History of Modern Wargames

If you've been following MMOBomb for a while, you probably know that I tend to cover nearly all the news related to war-themed free-to-play games, from Total War: Arena to Heroes & Generals to War Thunder to everything Wargaming makes. Magicman has even taken to calling me the site's “war correspondent.” Fittingly, I seem to wear out the soles of my shoes at an alarming rate, and during last week's rains, the leaks got so bad that my socks and feet were soaked after a walk, not unlike a doughboy in WWI having to spend all day and night in a trench during a downpour.

Wargaming – the concept, not the company – has likely existed in one form or another since people could wage war. The abstraction of battlefield tactics into a board game was the basis for chess and earlier games. I'm not looking for the origin of military-simulation-as-a-game in and of itself, however, but at the origin of something that vaguely resembles modern wargames, with at least semi-realistic units representing infantry, cavalry, artillery, and so on. As I dug into the past, I found a few ways in which the earliest wargames resemble modern video games.

A Wells-traveled Path

Wargames served as a major influence for role-playing games, with Dungeons & Dragons being partially inspired by Gary Gygax's Chainmail, a set of miniatures rules for medieval combat. So, on some level, you have wargames to thank not only for your military-themed games, but also for every MMORPG you play. They all have the same distant ancestors.

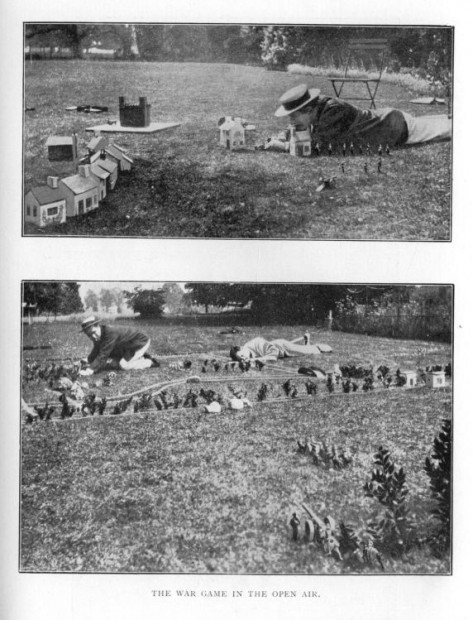

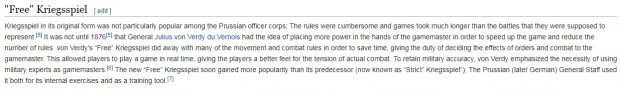

One of those most influential ancestors was H.G. Wells' Little Wars, a tome so important to the genre's development that Wells has been dubbed “the father of miniature wargaming.” Known mostly as a pioneering author of science fiction (The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, The Island of Doctor Moreau), Herbert George Wells published Little Wars in 1913. It was a manual that established formal rules for, well, playing with toy soldiers and having them shoot each other. In fact, it was the recent (at the time) development of the spring breechloader gun that made such a creation possible. Wells described it as

“This priceless gift to boyhood appeared somewhen towards the end of the last century, a gun capable of hitting a toy soldier nine times out of ten at a distance of nine yards.”

With this fabulous new technology, Wells engaged a friend, Jerome K. Jerome, in contests of miniature marksmanship. Another man, “Mr. W,” came up with the idea of using books and other items to form obstacles for the soldiers, an activity that was interrupted by the arrival of some women, who “regarded the objects upon the floor with the empty disdain of their sex for all imaginative things.”

(As a product of its times, Little Wars was unabashedly sexist, as can be seen in its full title, “A Game for Boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys' games and books.”)

One thing led to another, and before long Wells and his comrades were building elaborate sets indoor and out. If you're an adult who's ever been chided for playing “children's games,” you're in good company. While I was unable to find any evidence of Wells ever living in his parents' basement, he said that witnesses to his and his friends' miniature battles were

“unfavourably impressed by the spectacle of two middle-aged men playing with 'toy soldiers' on the floor, and very heated and excited about it.”

“Very heated and excited about it”? I wonder if Wells ever shouted obscenities or accused another player of hacking.

Wells discusses both the origin of his game and its development as it went through as he and his friends iterated endlessly on the rules. Nearly a century before the internet came into common usage, H.G. Wells might have written the first ever dev blog. And while he couldn't exactly upload to YouTube, this reads like what you might expect to see in a three-minute trailer from Call of Duty or Battlefield:

Little Wars was itself preceded by Wells' Floor Games, written in 1911 and with less formal rules, intended for a younger audience. But those weren't the first times someone tried laying down a rigid set of guidelines for conducting mock battles.

The Prussian Revolution

Following a description of the rules of the game and a narrative of a battle, Wells concludes Little Wars with an appendix that talks about its relationship to Kriegsspiel. While I had heard of Little Wars, this title was unfamiliar to me, though I knew enough German to understand its meaning: krieg = war and spiel = game.

According to Wikipedia, Kriegsspiel was “a system used for training officers in the Prussian and German armies.” It was concocted in 1812 – a full century before Wells' later works – by Prussian Lieutenent Georg Leopold von Reiswitz and his son Georg Heinrich Rudolf von Reiswitz. It was meant as a serious exercise for Prussian officers and was not meant for civilian use.

Kriegsspiel resembled modern tabletop wargaming in many ways, with different units, dice, terrain, movement rules, and a “fog of war” that kept players from knowing what their enemies were up to. A judge or umpire mediated the action.

At first, it wasn't very popular among the Prussian officer corps, however, leading me to this passage in the Wikipedia article, which is hilarious if read from a certain point of view:

Nearly 150 years ago, the very first wargame was “dumbed down for the casuals.” The hardcore l33t players have been complaining ever since.

Kriegsspiel not only had an effect on gaming, but arguably on world history. One of its proponents was Prussian Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Elder. He introduced it to none other than the kaiser himself, who, according to this account, “ordered a copy of the game for every one of his regiments.” That website also attests that the game's popularity might have been responsible for Prussia's victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Modern versions of the game are now available.

Footnote 1: von Moltke is probably best known for his famous quote (or variations thereof): “No plan survives contact with the enemy.”

Footnote 2: I do not suggest you follow in the Prussian army's footsteps and try to use Call of Duty-style tactics if you should ever find yourself in an actual war. Bullets hurt, and the damage can't be mended in a few seconds by finding a pile of bandages.

Wargames-as-analogs-to-actual-war not only predate World of Tanks and World of Warplanes – they predate tanks and planes, period. They started as training exercises for officers 200 years ago and stayed mostly in that form for a century before H.G. Wells made them more palatable for civilian enthusiasts. He, von Moltke, and von Reiswitz likely could never have imagined what their fiddling around with tiny toys on a tabletop or lawn could have led to through the years. Maybe we should invite them all to E3 next week.

Related Articles

About the Author

Jason Winter is a veteran gaming journalist, he brings a wide range of experience to MMOBomb, including two years with Beckett Media where he served as the editor of the leading gaming magazine Massive Online Gamer. He has also written professionally for several gaming websites.

More Stories by Jason WinterRead Next

I'm charitable enough to usually give a game a second chance if it don't hook me the first time around.

You May Enjoy

Learn how to master the kit of Rogue, the latest Marvel Rivals Vanguard to join the roster in Season 5.5

But is it too late?

And a free S-Rank character.

If you’ve been wondering who this Durin kid is, this is your answer.

If you or other mmobombers are interested in this stuff "Playing at the World" by Jon Peterson is a good read which starts with Kriegsspiel and goes through Little wars and Chainmail and how they lead to D&D, Gencon, RPGs and gaming in general.